This is a story that begins, “Once upon a time.”

But first, because this is a story about how the fundamentals of advertising and journalism are converging, here’s the lead: The old one-too-many model that is the foundation of both journalism and advertising is being eclipsed by a democratization of media, where communication now runs both ways and consumers demand 24/7 access and total transparency. Both industries are kinda freaking out.

Now on to the story.

Once upon a time, there were people who felt a duty to tell other people true stories about things that were happening. It was called the news. The people knew the truth and things were good.

In those same days, there was a very different group of people who wanted to tell other people about things that were happening. They told stories about how certain oils or tinctures would cure people of sickness. And later they told stories about how certain cars or clothes would make you happier and more popular at dinner parties. Sometimes those stories were true, sometimes the truth was stretched a little for effect. It was called advertising. The people paid for cool products and services that mostly did what they were supposed to do, and things were also pretty good.

And sometimes people talked to each other. They told both true and not-true stories about pretty much everything. They especially talked about the news and whether or not their latest vial of snake oil was reducing the swelling at all. It was called word of mouth. Sometimes it was good, and sometimes it was not.

All those things existed in parallel for many, many years. That is, until someone invented the internet.

Around 2002, social media went mainstream. It began its evolution into a prolific source for news and stories, among other things.

Social networks are nothing new. Human communication has existed in an ecosystem of stories within social groups since the beginning of… well, humans. But not until these new times could those stories cross borders, rivers, oceans and languages.

Across social media, people read things and they shared them with their friends. Some things were true, some things were not. But regardless of the level of true-ness in those stories, the public was liberated from its strict ration of twice-daily news. And as friends shared experiences with friends, the voices of companies and brands began to lose their opacity (and authority). The flood gates opened. People became interconnected on a global scale. And everyone with a dial-up connection became a reporter.

*cue dramatic music*

People began to report their own experiences, from their own perspectives. They had unprecedented and intimate access to almost everything that happened. Everything.

Suddenly, no one was buying the paper anymore. No one was paying for news at all. Ad dollars dried up, and the publications started shrinking. Some of the smaller shops disappeared altogether.

OK, it wasn’t that dramatic. But a lot of papers closed up shop and people lost their jobs. And that’s no joke.

The bigger houses took their publications online. They believed they’d coast on the credibility of the establishment. The honor of journalism. But they, too, struggled to survive on the antiquated ad model.

Meanwhile, in advertising land, companies were feeling the squeeze, too. Shiny new smartphones were really distracting people from commercials. Some people weren’t watching TV anymore at all. And even worse, the public was becoming increasingly suspicious of oils and tinctures that promised a cure for all that ailed them.

But what does snake oil have to do with the price of tea in China? This, my friends, is the moment where advertising and journalism converged.

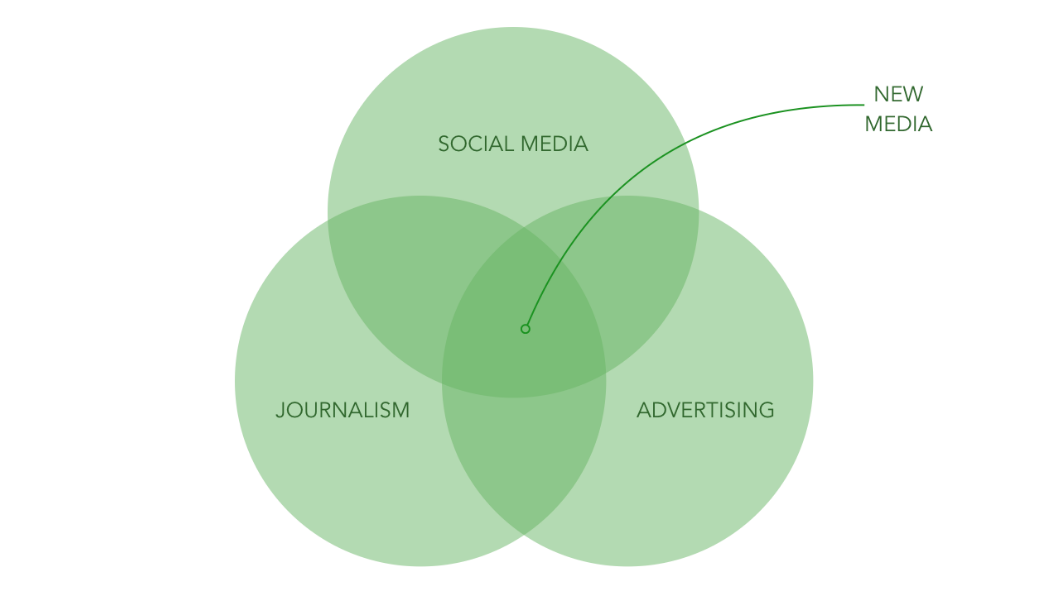

- Journalism possessed all the things that advertising lacked: Speed, relevance, and credibility.

- Advertising had the one thing news could never quite master: Creativity.

- Social media gave both news and advertising their most precious wish: Intimate access to consumers.

Brands figured out pretty quickly that when people share something with a friend, that friend almost always believes it’s true. That friend often shares it with a few more friends. And so on. They also figured out that when people are entertained, touched, scared or even really pissed off, they tend to want to buy whatever it is you’re selling.

Companies rushed to Facebook and Twitter to sell their oils and tinctures and dinner party–enhancement services. But it was too little, too late. Consumers had developed an insatiable appetite for truth and an incredibly sensitive bullshit meter. So brands had to make a choice: shame the Devil or face a long, slow death.

You may have noticed I tend toward the theatrical. Bear with me.

Thus begins the risky business of honesty.

But first, one more trip back in time. Long ago, (even before the beginning of this article), people in the news learned how to tell a story quickly. They had to. Telegraphs were pretty expensive, apparently, and people had to conserve their letters.

Those news stories were true and they were timely. Fast forward 100-or-so years: Elbow-deep in social media, brands are starting to feel the same pressures. Today’s internet is a modern day telegraph. Social media moves quickly. Letters are expensive. Tweets fill up fast. Composing the perfect subject line can make or break your email campaign.

But time and space aren’t the scariest part. Turns out, telling the truth is even more terrifying. In news, the story is the story. And journalists make it their mission to tell the stories that people want to hear. The stories that impact them the most.

In advertising… ehhhh notsomuch.

So how do we lay down the bullshit and abandon marketing garbage-speak? How do we save the dignity of words like “honesty” and “authenticity?”

Here are three quick best practices you can put into use immediately. Like, right now:

- Less talk, more listen

- Less product, more brand

- Less “buy, more “buy into”*

Because once we stop pretending to be storytellers, we can start actually telling stories.

…and they lived happily ever after.

###

*This is a concept I’ve practiced for years, but recently had the pleasure of hearing @petefavat articulate perfectly.